Dream of the Red Chamber

| Dream of the Red Chamber 紅樓夢 |

|

|---|---|

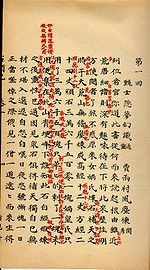

One page of the Jiaxu edition of Dream of the Red Chamber |

|

| Author | Cao Xueqin |

| Country | China |

| Language | Chinese |

| Genre(s) | Novel |

| Publication date | 18th century |

| Published in English |

1973–1980 (1st complete English translation) |

| Media type | Scribal copies/Print |

Dream of the Red Chamber (simplified Chinese: 红楼梦; traditional Chinese: 紅樓夢; pinyin: Hóng Lóu Mèng; Wade–Giles: Hung Lou Meng), composed by Cao Xueqin, is one of China's Four Great Classical Novels. It was composed sometime in the middle of the 18th century during the Qing Dynasty. It is a masterpiece of Chinese vernacular literature and is generally acknowledged to be the pinnacle of classical Chinese novels. "Redology" is the field of study devoted exclusively to this work.[1][2][3]

The novel's name may alternatively be translated as Red Chamber Dream or A Dream of Red Mansions, and it is sometimes referred to by another name, The Story of the Stone (simplified Chinese: 石头记; traditional Chinese: 石頭記; pinyin: Shítóu jì; literally "Record of the Stone").

Red Chamber is believed to be semi-autobiographical, mirroring the fortunes of author Cao Xueqin's own family. As the author details in the first chapter, it is intended to be a memorial to the women he knew in his youth: friends, relatives and servants. The novel is remarkable not only for its huge cast of characters and psychological scope, but also for its precise and detailed observation of the life and social structures typical of 18th-century Chinese aristocracy.[4]

Contents |

Language

The novel is written in vernacular rather than classical Chinese and helped establish the legitimacy of the vernacular idiom. Its author, Cao Xueqin, was well versed in Chinese poetry and in classical Chinese, having written tracts in the erudite semi-wenyan style. The novel's conversations were written in the Beijing Mandarin dialect, which was to become the basis of modern spoken Chinese, with influences from Nanjing-area Mandarin (where Cao's family lived in the early 1700s).

Themes

The novel is normally called Hung Lou Meng or Hóng Lóu Mèng (紅樓夢), literally "Red chamber dream". "Red tower" or "red chamber" is an idiom for the sheltered chambers where the daughters of wealthy families lived.[5] It also refers to a dream in Chapter 5 that Baoyu has, set in a "red chamber", where the fates of many of the characters are foreshadowed. "Chamber" is sometimes translated as "mansion" because of the scale of the Chinese word "樓", but "mansion" is thought to neglect the flavour of the word "chamber" and it is a mistranslation according to Zhou Ruchang.[6][7]

The name of the main family, "賈", is a homophone with another Chinese character "假", which means false, fake, fictitious or sham. Thus, Cao Xueqin suggests that the novel's family is both a realistic reflection and a fictional or "dream" version of his own family.

Plot summary

The novel provides a detailed, episodic record of the two branches of the Jia (賈) clan — the Rongguo House (榮國府) and the Ningguo House (寧國府) — who reside in two large, adjacent family compounds in the capital. Their ancestors were made dukes, and as the novel begins the two houses are among the most illustrious families in the capital. One of the clan’s offspring is made an Imperial Consort, and a gigantic landscaped interior garden, named the Prospect Garden, is built to receive her visit. The novel describes the Jias’ wealth and influence in great naturalistic detail, and charts the Jias’ fall from the height of their prestige, following some thirty main characters and over four hundred minor ones. Eventually the Jia clan falls into disfavor with the Emperor, and their mansions are raided and confiscated.

In the story‘s preface, a sentient Stone, abandoned by the Goddess Nüwa when she mended the heavens aeons ago, begs a Taoist priest and Buddhist monk to bring it with him to enjoy in the worldly world. The Stone and Divine Attendant-in-Waiting (神瑛侍者) are separate beings (while in Cheng-gao versions they are merged into the same character).

The main character, Jia Baoyu (whose name means "precious jade"), is the adolescent heir of the family, a reincarnation of the Divine Attendant-in-Waiting. The Crimson Pearl Fairy (絳珠仙子) is incarnated as Baoyu's sickly cousin, the emotional Lin Daiyu, who loves Baoyu. Baoyu, however, is predestined in this life to marry another cousin, Xue Baochai. This love triangle against the backdrop of the family's declining fortunes forms the most well-known plot line in the novel.

Reception and Interpretation

From the first manuscripts circulating from the year 1759 until today, the novel has been a continuously successful bestseller not only in China, but all over the world in its various translations. One reason is that the story describes the unwillingness of a young man to grow up, a particularly resonant theme in literature. When the young man, Jia Baoyu, finally grows up, the paradise-like Prospect Garden of his childhood is destroyed and his friends are scattered to the four winds.[8]

Characters

Dream of the Red Chamber contains an extraordinarily large number of characters: nearly thirty are considered major characters, and there are over four hundred additional ones.[9] Jia Baoyu is the male protagonist. Females take center stage and are frequently shown to be more capable than their male counterparts. The names of the maids and bondservants are given in the original pinyin pronunciations and in David Hawkes' translation.

Baoyu and Jinling's Twelve Beauties

- Jia Baoyu (simplified Chinese: 贾宝玉; traditional Chinese: 賈寶玉; pinyin: Jiǎ Bǎoyù; Wade–Giles: Chia Pao-yu, Meaning: Precious Jade)

The main protagonist, he is about 12- or 13-years-old when he is introduced in the novel.[10] The adolescent son of Jia Zheng (賈政) and his wife, Lady Wang (王夫人). Born with a piece of luminescent jade in his mouth (the Stone), Baoyu is the heir apparent to the Rongguo line (榮國府). Frowned on by his strict Confucian father, Baoyu reads Zhuangzi and Romance of the West Chamber rather than the Four Books basic to a classic Chinese education. Baoyu is highly intelligent, but hates the fawning bureaucrats that frequent his father's house. He shuns ordinary men, considering them morally and spiritually inferior to women. Sensitive and compassionate, Baoyu holds the view that "girls are in essence pure as water, and men are in essence muddled as mud." The book even indicates that he has had sexual affairs with some of his maids including Xiren. His surname Jia is a homonym for "False" and a boy named Zhen Baoyu ("True Baoyu") makes an appearance in the book.

- Lin Daiyu (Chinese: 林黛玉; pinyin: Lín Dàiyù; Wade–Giles: Lin Tai-yu, Meaning: Black Jade)

Jia Baoyu's younger first cousin and his primary love interest. She is the daughter of Lin Ruhai (林如海), a Yangzhou scholar-official, and Lady Jia Min (賈敏), Baoyu's paternal aunt. She is thin, sickly, but beautiful in a way that is unconventional. She also suffers from a respiratory ailment which makes her cough. The novel proper starts in Chapter 3 with Daiyu's arrival at the Rongguo House shortly after the death of her mother. Fragile emotionally, prone to fits of jealousy, Daiyu is nevertheless an extremely accomplished poet and musician. The novel designates her one of the Jinling Twelve Women, and describes her as a lonely, proud and ultimately tragic figure. Daiyu is the reincarnation of the Crimson Pearl Flower, and the purpose of her mortal birth is to repay Baoyu (for watering her) with her tears.

- Xue Baochai (simplified Chinese: 薛宝钗; traditional Chinese: 薛寶釵; pinyin: Xuē Bǎochāi; Wade–Giles: Hsueh Pao-chai, Meaning: Precious Virtue)

Jia Baoyu's other first cousin. The only daughter of Aunt Xue (薛姨媽), sister to Baoyu's mother, Baochai is a foil to Daiyu. Where Daiyu is unconventional and hypersensitive, Baochai is sensible and tactful: a model Chinese feudal maiden. The novel describes her as beautiful and intelligent, but also reserved and following the rules of decorum. Although reluctant to show the extent of her knowledge, Baochai seems to be quite learned about everything, from Buddhist teachings to how not to make a paint plate crack. She is not keen on elaborately decorating her room and herself. The novel describes her room as being completely free of decoration, apart from a small vase of chrysanthemums. Baochai has a round face, fair skin, large eyes, and, some would say, a voluptuous figure in contrast to Daiyu's willowy daintiness. Baochai carries a golden locket with her which contains words given to her in childhood by a Buddhist monk. Baochai's golden locket and Baoyu's jade contain inscriptions that appear to complement one another perfectly. Their marriage is seen in the book as predestined.

- Jia Yuanchun (simplified Chinese: 贾元春; traditional Chinese: 賈元春; pinyin: Jiǎ Yuánchūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Yuan-chun, Meaning: First of Spring)

Baoyu's elder sister by about a decade. Originally one of the ladies-in-waiting in the imperial palace, Yuanchun later becomes an Imperial Consort, having impressed the Emperor with her virtue and learning. Her illustrious position as a favorite of the Emperor marks the height of the Jia family's powers. Despite her prestigious position, Yuanchun feels imprisoned within the four walls of the imperial palace. Redologists think that in the original lost ending, Yuanchun's sudden death precipitates the fall of the Jia family.

- Jia Tanchun (simplified Chinese: 贾探春; traditional Chinese: 賈探春; pinyin: Jiǎ chūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Tan-chun, Meaning: Quest of Spring)

Baoyu's younger half-sister by Concubine Zhao. Brash and extremely outspoken, she is almost as capable as Wang Xifeng. Wang Xifeng herself compliments her privately, but laments that she was "born in the wrong womb," since concubine children are not respected as much as those by first wives. She is also a very talented poet. Tanchun is nicknamed "Rose" for her beauty and her prickly personality.

- Shi Xiangyun (simplified Chinese: 史湘云; traditional Chinese: 史湘雲; pinyin: Shǐ Xiāngyún; Wade–Giles: Shih Hsiang-yun, Meaning: Xiang River Mist)

Jia Baoyu's younger second cousin. Grandmother Jia's grandniece. Orphaned in infancy, she grows up under her wealthy maternal uncle and aunt who use her unkindly. In spite of this Xiangyun is openhearted and cheerful. A comparatively androgynous beauty, Xiangyun looks good in men's clothes (once she put on Baoyu's clothes and Grandmother Jia thought she was he), and loves to drink and eat barbecued meat. She is forthright and without tact, but her forgiving nature takes the sting from her casually truthful remarks. She is well educated and as talented a poet as Daiyu or Baochai.

- Miaoyu (Chinese: 妙玉; pinyin: Miàoyù; Wade–Giles: Miao-yu, Meaning: Wonderful/Clever Jade)

a young nun from Buddhist cloisters of the Rong-guo house. Extremely beautiful and learned, while also extremely aloof, haughty and unsociable. She also has an obsession with cleanliness. The novel says she was compelled by her illness to become a nun, and shelters herself under the nunnery in Prospect Garden to dodge political affairs. She likes Zhuangzi's articles.

- Jia Yingchun (simplified Chinese: 贾迎春; traditional Chinese: 賈迎春; pinyin: Jiǎ Yíngchūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Ying-chun, Meaning: Welcome Spring)

Second female family member of the generation of the Jia household after Yuanchun, Yingchun is the daughter of Jia She, Baoyu's uncle and therefore his elder first cousin. A kind-hearted, weak-willed person, Yingchun is said to have a "wooden" personality and seems rather apathetic toward all worldly affairs. Although very pretty and well-read, she does not compare in intelligence and wit to any of her cousins. Yingchun's most famous trait, it seems, is her unwillingness to meddle in the affairs of her family. Eventually Yingchun marries a new favorite of the imperial court, her marriage being merely one of her father's desperate attempts to raise the declining fortunes of the Jia family. The newly married Yingchun becomes a victim of domestic abuse and constant violence at the hands of her cruel, abusive husband.

- Jia Xichun (simplified Chinese: 贾惜春; traditional Chinese: 賈惜春; pinyin: Jiǎ Xīchūn; Wade–Giles: Chia Hsi-chun, Meaning: Compassion Spring)

Baoyu's younger second cousin from the Ningguo House, but brought up in the Rongguo House. A gifted painter, she is also a devout Buddhist. She is the sister of Jia Zhen, head of the Ningguo House. At the end of the novel, after the fall of the house of Jia, she gives up her worldly concerns and becomes a Buddhist nun. She is the second youngest of Jinling's Twelve Beauties, described as a pre-teen in most parts of the novel.

- Wang Xifeng (simplified Chinese: 王熙凤; traditional Chinese: 王熙鳳; pinyin: Wáng Xīfèng; Wade–Giles: Wang Hsi-feng, Meaning: Splendid Phoenix), alias Sister Feng.

Baoyu's elder cousin-in-law, young wife to Jia Lian (who is Baoyu's paternal first cousin), niece to Lady Wang. Xifeng is hence related to Baoyu both by blood and marriage. An extremely handsome woman, Xifeng is capable, clever, amusing and, at times, vicious and cruel. Undeniably the most worldly of the women in the novel, Xifeng is in charge of the daily running of the Rongguo household and wields remarkable economic as well as political power within the family. Being a favorite of Grandmother Jia, Xifeng keeps both Lady Wang and Grandmother Jia entertained with her constant jokes and amusing chatter, playing the role of the perfect filial daughter-in-law, and by pleasing Grandmother Jia, ruling the entire household with an iron fist. One of the most remarkable multi-faceted personalities in the novel, Xifeng can be kind-hearted toward the poor and helpless. On the other hand, Xifeng can be cruel enough to kill. Her feisty personality, her loud laugh, and her great beauty contrast with many of the frail, weak-willed beauties of the literature of 18th-century China.

- Jia Qiaojie (simplified Chinese: 贾巧姐; traditional Chinese: 賈巧姐; pinyin: Jiǎ Qiǎojiě; Wade–Giles: Chia Chiao-chieh, Meaning: Timely Older Sister)

Wang Xifeng's and Jia Lian's daughter. She is a child through much of the novel. After the fall of the house of Jia, in the version of Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan, she marries the son of a wealthy rural family introduced by Granny Liu and goes on to lead a happy, uneventful life in the countryside.

- Li Wan (simplified Chinese: 李纨; traditional Chinese: 李紈; pinyin: Lǐ Wán; Wade–Giles: Li Wan, Meaning: White Silk)

Baoyu's elder sister-in-law, widow of Baoyu's deceased elder brother, Jia Zhu (賈珠). Her primary task is to bring up her son Lan and watch over her female cousins. The novel portrays Li Wan, a young widow in her late twenties, as a mild-mannered woman with no wants or desires, the perfect Confucian ideal of a proper mourning widow. She eventually attains high social status due to the success of her son at the Imperial Exams, but the novel sees her as a tragic figure because she wasted her youth upholding the strict standards of behavior.

- Qin Keqing (Chinese: 秦可卿; pinyin: Qín Kěqīng; Wade–Giles: Ch'in Ko-ching)

Daughter-in-law to Jia Zhen. Of all the characters in the novel, the circumstances of her life and early death are amongst the most mysterious. Apparently a very beautiful and flirtatious woman, she carried on an affair with her father-in-law and dies before the second quarter of the novel. Her bedroom is bedecked with priceless artifacts belonging to extremely sensual women, both historical and mythological. In her bed, Bao Yu first travels to the Land of Illusion where he has a sexual encounter with Two-In-One, who represents Xue Baochai and Lin Daiyu. Two-in-One's name is also Keqing, making Qin Keqing also a significant character in Bao Yu's sexual experience. The original twelve songs hint that Qin Keqing hanged herself.

Other main characters

- Grandmother Jia (simplified Chinese: 贾母; traditional Chinese: 賈母; pinyin: Jiǎmǔ), née Shi.

Also called the Matriarch or the Dowager, the daughter of Marquis Shi of Jinling. Grandmother to both Baoyu and Daiyu, she is the highest living authority in the Rongguo house and the oldest and most respected of the entire clan, yet also a doting person. She has two sons, Jia She and Jia Zheng, and a daughter, Min, Daiyu's mother. Daiyu is brought to the house of the Jias at the insistence of Grandmother Jia, and she helps Daiyu and Baoyu bond as childhood playmates and, later, kindred spirits.

- Jia She (simplified Chinese: 贾赦; traditional Chinese: 贾赦; pinyin: Jiǎ Shè; Wade–Giles: Chia Sheh, Meaning: "To Pardon")

The elder son of the Dowager. He is the father of Jia Lian and Jia Yingchun. He is a treacherous and greedy man, and an extreme womanizer.

- Jia Zheng (simplified Chinese: 贾政; traditional Chinese: 賈政; pinyin: Jiǎ Zhèng; Wade–Giles: Chia Cheng, Meaning: "Political/Governance")

Baoyu's father, the younger son of the Dowager. He is a disciplinarian and Confucian scholar. Afraid his one surviving son will turn bad, he imposes strict rules on his son, and uses occasional corporal punishment. He has a wife, Lady Wang, and two concubines: Zhao and Zhou.

- Jia Lian (simplified Chinese: 贾琏; traditional Chinese: 賈璉; pinyin: Jiǎ Lián; Wade–Giles: Chia Lien, Meaning: "Vessel for Grain at Ancestral Temples")

Xifeng's husband and Baoyu's paternal elder cousin, a notorious womanizer whose numerous affairs cause much trouble with his jealous wife, including affairs with men that are not known by his wife. His pregnant concubine (Second Sister You) eventually dies by his wife's engineering. He and his wife are in charge of most hiring and monetary allocation decisions, and often fight over this power.

- Xiangling (香菱, "Fragrant Water Caltrop") — the Xues' maid, born Zhen Yinglian (甄英蓮, literally "The real outstanding lotus", a homophone with "deserving pity"), the kidnapped and lost daughter to Zhen Shiyin (甄士隱), the country gentleman in Chapter 1. Her name is changed to Qiuling (秋菱) by Xue Pan's spoiled wife, Xia Jin'gui (夏金桂).

- Ping'er (平兒, "Peaceful")

Xifeng's chief maid and personal confidante; also concubine to Xifeng's husband, Jia Lian. The consensus among the novel's characters seem to be that Pinger is beautiful enough to rival the mistresses in the house. Originally Xifeng's maid in the Wang household, she follows Xifeng as part of her "dowry" when Xifeng marries into the Jia household. She handles her troubles with grace, assists Xifeng capably and appears to have the respect of most of the household servants. She is also one of the very few people who can get close to Xifeng. She wields considerable power in the house as Xifeng's most trusted assistant, but uses her power sparingly and justly.

- Xue Pan (Chinese: 薛蟠; pinyin: Xuē Pán; Wade–Giles: Hsueh Pan, Meaning: "To Coil (as a dragon)")

Baochai's older brother, a dissolute, idle rake who was a local bully in Jinling. He was known for his amorous exploits with both men and women. Not particularly well educated, he once killed a man over a servant-girl (Xiangling) and had the manslaughter case hushed up with money.

- Granny Liu (simplified Chinese: 刘姥姥; traditional Chinese: 劉姥姥; pinyin: Liú Lǎolao)

A country rustic and distant relation to the Wang family, who provides a comic contrast to the ladies of the Rongguo House during two visits. She eventually rescues Qiaojie from her maternal uncle, who wanted to sell her.

- Lady Wang (Chinese: 王夫人; pinyin: Wáng Fūren)

A Buddhist, primary wife of Jia Zheng. Because of her purported ill-health, she hands over the running of the household to her niece, Xifeng, as soon as the latter marries into the Jia household, although she retains overall control over Xifeng's affairs so that the latter always has to report to her. Although Lady Wang appears to be a kind mistress and a doting mother, she can in fact be cruel and ruthless when her authority is challenged. She pays a great deal of attention to Baoyu's maids to make sure that Baoyu does not develop romantic relationships with them.

- Aunt Xue (simplified Chinese: 薛姨妈; traditional Chinese: 薛姨媽; pinyin: Xuē Yímā), née Wang

Baoyu's maternal aunt, mother to Pan and Baochai, sister to Lady Wang. She is kindly and affable for the most part, but finds it hard to control her unruly son.

- Xiren (simplified Chinese: 袭人; traditional Chinese: 襲人; pinyin: Xírén, Meaning: "Assails Men")

Baoyu's principal maid and his unofficial concubine. Originally the maid of the Dowager, Xiren was given to Baoyu because of her extreme loyalty toward the master she serves. Considerate and forever worried about Baoyu, she is the partner of his first adolescent sexual encounter in the real world in Chapter 5.

- Qingwen (Chinese: 晴雯; pinyin: Qíngwén, Meaning: "Clear Mulitcolored Clouds")

Baoyu's handmaiden. Brash, haughty and the most beautiful maid in the household, Qingwen is said to resemble Daiyu very strongly. Of all of Baoyu's maids, she is the only one who dares to argue with Baoyu when reprimanded, but is also extremely devoted to him. She is disdainful of Xiren's attempt to use her sexual relation with Baoyu to raise her status in the family. Lady Wang later suspected her of having an affair with Baoyu and publicly dismisses her on that account; angry at the unfair treatment and of the indignities and slanders that attended her as a result, Qingwen dies of an illness shortly after leaving the Jia household.

- Yuanyang (Chinese: 鸳鸯; pinyin: Yuānyang, Meaning: "Mandarin Duck")

The Dowager's chief maid. She rejected a marriage proposal (as concubine) to the lecherous Jia She, Grandmother Jia's eldest son.

- Mingyan (simplified Chinese: 茗烟; traditional Chinese: 茗煙; pinyin: Míngyān, Meaning: "Tea Mist")

Baoyu's page boy. Knows his master like the back of his hand.

- Zijuan (simplified Chinese: 紫鹃; traditional Chinese: 紫鵑; pinyin: Zǐjuān; Wade–Giles: Tzu-chuan, Meaning: "Purple Cuckoo")

Daiyu's faithful maid, ceded by the Dowager to her granddaughter.

- Xueyan (Chinese: 雪雁; pinyin: Xuěyàn, Meaning: "Snowgoose")

Daiyu's other maid. She came with Daiyu from Yangzhou, and comes across as a young, sweet girl.

- Concubine Zhao (simplified Chinese: 赵姨娘; traditional Chinese: 趙姨娘; pinyin: Zhào Yíniáng)

A concubine of Jia Zheng. She is the mother of Jia Tanchun and Jia Huan, Baoyu's half-siblings. She longs to be the mother of the head of the household, which she does not achieve. She plots to murder Baoyu and Xifeng with black magic, and it is believed that her plot cost her her own life.

Notable minor characters

- Qin Zhong (秦鐘) — Qin Keqing's handsome younger brother. He looks like a girl as well as being as shy as a girl. He is a good friend and classmate to Baoyu, while the novel occasionally suggests that the relationship between the two might be more than just friends. He was bullied by another student at school, who say that he is homosexual. This turned the school upside-down when Baoyu and his servants try to defend Qin against the rogues. He has had a romantic relationship with a teenage nun later in the story. He dies young.

- Jia Lan (賈蘭) — Son of Baoyu's deceased older brother Jia Zhu and his virtuous wife Li Wan. Jia Lan is an appealing child throughout the book and at the end succeeds in the imperial examinations to the credit of the family.

- Jia Zhen (賈珍) — Head of the Ningguo House, the elder branch of the Jia family. He has a wife, Lady Yu, a younger sister, Jia Xichun, and many concubines. He is extremely greedy and the unofficial head of the clan, since his father has retired. He has an adulterous affair with his daughter-in-law, Qin Keqing.

- Lady You (尤氏) — wife of Jia Zhen. She is the sole mistress of the Ningguo House. You is also spelled as Yu.

- Jia Rong (賈蓉) — Jia Zhen's son. He is the husband of Qin Keqing. An exact copy of his father, he is the Cavalier of the Imperial Guards.

- Second Sister You (尤二姐) — Concubine to Jia Lian. She is a beautiful and modest young lady, a concubine who was treated so badly by Wang Xifeng that she commits suicide by swallowing gold. She is the elder sister of Third Sister You. You is also spelled Yu.

- Lady Xing (邢夫人) — Jia She's wife. She is Jia Lian's mother.

- Jia Huan (賈環) — son of Concubine Zhao. He and his mother are both reviled by the family, and he carries himself like a kicked dog. He shows his malign nature by spilling candle wax, intending to blind Bao Yu.

- Sheyue (麝月, Musk) — Baoyu's main maid after Xiren and Qingwen. She is beautiful and caring, a perfect complement to Xiren.

- Qiutong (秋桐) — Jia Lian's other concubine. Originally a maid of Jia She, she is given to Jia Lian as a concubine. She is a very proud and arrogant woman.

- Sister Silly (傻大姐) — a maid who does rough work for the Dowager. She is guileless but amusing and caring. In the Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan version, She unintentionally informs Daiyu of Baoyu's secret marriage plans.

Homophones

The homophones are one of the features of this book. In this book, many character and place names have a special meanings. Rouge Inkstone's note pointed out some of their hidden meanings. Homophones found by Redologies are marked with *.

- Huzhou (胡州) — Groundless speaking (胡謅)

- Zhen Shiyin (甄士隱) — That under which true things are hidden (真事隱)

- Zhen Yinglian (甄英莲, Zhēn Yīnglián) — Truly deserving pity (真應憐, Zhēn Yīnglián)

- Feng Su (封肅) — Custom (風俗)

- Huo Qi (霍啟) — Disaster starts / Fire is on* (禍起/火起)

- Jia (賈, the surname of the main family) - False, fake (假)

- Zhen (甄, the surname of the other main family) - Real, true (眞)

- Jia Yucun (賈雨村(號雨村)) — Unreal words exist* (假語存)

- Jia Hua (姓賈名化) - Unreal words (假話)

- Shifei (字時飛) - That which is not real after all (實非)

- Qing Keqing (秦可卿) — Sensation should be despised or Sensation can overthrow (情可輕 or 情可傾)*

- Yuanchun, Yingchun, Tanchun, Xichun (元迎探惜) — Originally, should sigh (原應嘆息)

- Dian'er (靛兒) — Scapegoat (墊兒)*

- Zhang Youshi (張友士) — Something is going to be on (将有事)*

- Jia Mei (賈玫) — Suppose disappear (假沒, 假設沒有這個人)*

- Wei Ruolan (衛若蘭, Wèi ruò) — The given name Ruolan (若蘭) means "like an orchid." The family name Wèi (衛) has the same pronunciation as 味, meaning "scent or taste." Wei Ruolan is then a homophone for "with a scent like an orchid."*

Versions

The textual problems of the novel are extremely complex and have been the subject of much critical scrutiny, debate and conjecture in modern times.[11] Cao did not live to publish his novel, and only hand-copied manuscripts survived after his death until 1791, when the first printed version was published. This printed version, known as the Chenggao edition, contains edits and revisions not authorised by the author.

Rouge versions

The novel was anonymous until the 20th century. After Hu Shi's analyses, it is generally agreed that Cao Xueqin wrote the first 80 chapters of the novel.

Up until 1791, the novel circulated merely in scribal transcripts. These early hand-copied versions end abruptly at the latest at the 80th chapter. The earlier ones furthermore contain transcribed comments and annotations in red ink from unknown commentators. These commentators' remarks reveal much about the author as a person, and it is now believed that some of them may even be members of Cao Xueqin's own family. The most prominent commentator is Rouge Inkstone (脂硯齋), who revealed much of the interior structuring of the work and the original manuscript ending, now lost. These manuscripts are the most textually reliable versions, known as Rouge versions (脂本). Even amongst some 12 independent surviving manuscripts, small differences in some of the characters, rearrangements and possible rewritings cause the texts to vary a little.

The early 80 chapters brim with prophecies and dramatic foreshadowings which also give hints as to how the book would continue. For example, it is obvious that Lin Daiyu will eventually die in the course of the novel; that Baoyu and Baochai will marry; that Baoyu will become a monk.

Most modern critical editions use the first 80 chapters based on the Rouge versions.

Cheng-Gao versions

In 1791 Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan brought together the novel's first movable type edition. This was also the first "complete" edition of The Story of the Stone, which they printed as Dream of the Red Chamber. While the original Rouge manuscripts have eighty chapters, ending roughly three-quarters of the way into the plot and clearly incomplete, the 1791 edition completed the novel in one hundred and twenty chapters. The first eighty chapters were edited from the Rouge versions, but the last forty were newly published.

In 1792, Chen and Gao published a second edition correcting many "typographical and editorial" errors of the 1791 version and with a now-famous preface. In the 1792 preface, the two editors claimed to have put together an ending based on the author's working manuscripts, which they bought from a street vendor.

The debate over the last forty chapters and the 1792 preface continues. Most modern scholars believe these chapters were a later addition, with plotting and prose inferior to the first eighty chapters. Hu Shih argued that the ending was simply forged by Gao E, citing the foreshadowing of the main characters' fates in Chapter 5, which does not agree with the ending of the 1791 Chenggao version.

Other critics suggest Gao E and Cheng Weiyuan were duped into taking someone else's forgery as an original work. A minority believe the last forty chapters contain Cao's work.

The book is normally published and read in Cheng Weiyuan and Gao E's one hundred and twenty chapter version. Some editions move the last forty chapters to an appendix. Also, some modern editions (like that of Zhou Ruchang's) do not include the last forty chapters.

Translations

- The Story of the Stone (first eighty chapters by David Hawkes and last forty by John Minford), Penguin Classics or Bloomington: Indiana University Press, five volumes, 1973–1980. ISBN 0-14-044293-6, ISBN 0-14-044326-6, ISBN 0-14-044370-3; ISBN 0-14-044371-1, ISBN 0-14-044372-X. This is considered by many, including Gladys Yang (who also translated the work), as the best available version.[1]

- The Dream of the Red Chamber (David Hawkes), New York: Penguin Group 1996. ISBN 0146001761. Highly abridged.

- A Dream of Red Mansions (Gladys Yang and Yang Hsien-yi) Beijing: Foreign Language Press, four volumes, 1978–1980.

- Dream of the Red Chamber (Wang Chi-Chen), abridged, largely translated in 1929, then augmented for publication in 1958. ISBN 0385093799.

- Hung Lou Meng (H. Bencraft Joly), from the Gutenberg Project, Hong Kong: Kelly & Walsh, 1892–1893, paper published edition is also available. Wildside Press, ISBN 0809592681; and Hard Press, November 3, 2006, ISBN 1406940798.

- Red Chamber Dream (Dr. B.S. Bonsall), Unpublished typescript. Available on the web.

- The Dream of the Red Chamber (Florence and Isabel McHugh), abridged, which follows the German translation of Franz Kuhn. 1958, ISBN 0837181135.

See also

- Redology

- Rouge Inkstone

- Odd Tablet

Notes

- ↑ Cao Xueqin. 红楼梦. 百花文艺出版社. p. 1. ISBN 7530628151. "……《红楼梦》,不仅是中国小说史,而且是中国文学史上思想和艺术成就最高、对后世文学影响最为深远巨大的经典作品。"

- ↑ Cao Xueqin. 红楼梦. 人民出版社. inside front cover. ISBN 9787010060187. "《红楼梦》被公认为中国古典小说的巅峰之作。"

- ↑ Li Liyan. "The Stylistic Study of the Translation of A Dream of Red Mansions". http://dlib.cnki.net/kns50/detail.aspx?filename=2003051540.nh&dbname=CMFD2002&filetitle=%E3%80%8A%E7%BA%A2%E6%A5%BC%E6%A2%A6%E3%80%8B%E8%8B%B1%E8%AF%91%E6%9C%AC%E7%9A%84%E6%96%87%E4%BD%93%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B6. "伟大不朽的古典现实主义作品《红楼梦》是我国古典小说艺术成就的最高峰。" (Chinese)

- ↑ CliffsNotes, About the Novel: Introduction

- ↑ 词语“红楼”的解释 汉典

- ↑ Zhou, Ruchang. 红楼夺目红. 作家出版社. pp. 4. ISBN 7506327082.

- ↑ Zhou, Ruchang. 红楼小讲. 中华书局. pp. 200. ISBN 9787101055665.

- ↑ Martin Woesler, Preface, in: Tsau, Hsüä-Tjin / Gau, E: The Dream of the Red Chamber or the Story of the Stone, transl. by Rainer Schwarz, Martin Woesler, ed., European University Press 2007-2009, 3 vols., 2640 pp, vol. 1, p x

- ↑ Yang, Weizhen; Guo, Rongguang (1986). 《红楼梦》辞典. 山东文艺出版社. Introduction. There are entries for 447 named characters. ISBN 7-5329-0078-9.

- ↑ Cao, Xueqin; Gao E. "Chapter 23". Hong Lou Meng.

- ↑ Dore Jesse Levy: Ideal and Actual in The Story of the Stone, p 7.

References

- Zhou Ruchang, Between Noble and Humble: Cao Xueqin and the Dream of the Red Chamber, ISBN 978-1433104077

- Jonathan D. Spence, The Search for Modern China, ISBN 0-393-30780-8

- Cao, Xueqin. The Story of the Stone: a Chinese Novel: Vol 1, The Golden Days. trans. David Hawkes. ISBN 0-14-044293-6.

- Cao, Xueqin. The Story of the Stone: a Chinese Novel: Vol 2, The Crab-flower Club. trans. David Hawkes. ISBN 0-14-044326-6.

- Cao, Xueqin. The Story of the Stone: a Chinese Novel: Vol 3, The Warning Voice. trans. David Hawkes. ISBN 0-14-044370-3.

- Tsao Hsueh-Chin (Cao Xueqin), Dream of the Red Chamber, Translated & abridged by Chi-Chen Wang, Doubleday Anchor, 1958. ISBN 0-38-509379-9

External links

Translations

- Hung Lou Meng Vol. 1, Vol. 2 by H. Bencraft Joly

- Red Chamber Dream by Bramwell Seaton Bonsall (Unpublished typescript)

Annotations

- Dream of the Red Chamber annotated edition with mouseover popups (English definitions for every single word in the entire first chapter)

Other links

- Book summary and analyses from CliffsNotes

- An Introduction to Editions of the Red Chamber, David L. Steelman, The Scholar, 1981

- Outline of Dream of the Red Chamber

- Red on Gold: Teaching Honglou meng in California

- Article on China Central Television Program about Red Chamber - China Daily. Raymond Zhou. November 12, 2005.

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||